When I was much younger, early twenties I think, we lost our stepfather Hamish to a heart attack.

He was only young, 47. A tall lean farmer with a ready smile and cheeky quip. Hamish was likeable and seemed fit, so it was all a complete shock when he fell dead from a massive heart attack as he drank his coffee at work. He was apparently dead before he hit the ground.

Just the evening before I had been helping him fix oily bits on the old VW beetle the folks had bought for us kids.

I remembered that day vividly.

We had an American exchange student at the time named Chase. Chase received the news first as I cycled home from university. “Pete, Pete, Hamish is dead!” yelled Chase as he sprinted towards me down our long driveway. Poor Chase, he’d only been with us a few weeks.

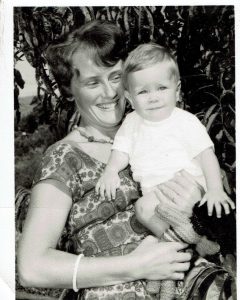

My mother, Mary, flew home that night from a conference of some sort. My grandfather and I met and collected her from the airport. I remember Mum trying to be so stoic as she walked off the plane towards us then bursting into tears as she drew nearer.

No-one should ever see their mother that broken.

Hamish was the first dead body I’d ever seen.

He looked so ‘normal’, asleep, but cold. I noticed the small things, like the grease under his fingernails from fixing the VW. I didn’t want to touch him. I felt bad afterwards that I hadn’t, like I’d insulted him somehow. Sorry Hamish.

Hamish was cremated.

He was handed back to my mother in a grey rectangular plastic box.

Plastic! How . . . commercial.

The box was surprisingly heavy.

Hamish was interred at our local memorial gardens.

Mum had it all planned. Her parents were there near each other with brass plaques denoting their name and position beneath red roses within immaculately groomed circular gardens.

Hamish wasn’t a rose guy, so Mum chose a position beneath a huge oak tree.

Mum said she would visit him all the time.

I was sceptical. Really? ‘All the time’ is a lot of times. But I held my tongue.

I did, however, enquire how the Hamish visits were going after about a year.

Mum replied a little sheepishly that she didn’t have the time to visit Hamish much, but brightened as she announced that she tooted the car horn as she drove by.

People must have thought Mum was crazy, beeping her car horn randomly on a motorway . . .

I do remember thinking, though, is that all we’re destined to be reduced to, if we’re lucky, a toot of a horn?

Toot toot.

Then life simply gets in the way.

And we were lucky, those memorial gardens were relatively close by.

What about all those cemeteries in the countryside? Full of the deceased few will ever see again nor remember.

I recall a quote I think attributed to Hemingway, he said it best – Every man has two deaths, when he is buried in the ground and the last time someone says his name.

It really did have me wondering about how we handle, celebrate and remember our forebears. Some cultures do it much better than others.

I read once about the Japanese ashes ceremony Kotsuage. Family members take turns with long chopsticks to transfer the cremated remains of a relative into an urn. Bone fragments have to be put into the urn in strict order, feet first to keep the person upright. Everyone does it, Kids and all!

The point of Kotsuage I presume is that everyone takes their time and talks, I would hope with fondness, about the recently passed away relative. It’s their form of remembrance. I’d remember my grandparent acutely too if I had to place a toe bone into an urn.

In any case I have my toot toot memory to remind me of Hamish and his grease beneath his fingernails.

That experience along with others bounced around inside my head for years, which helped inform a mad idea about compressing ashes and keeping them nearby.

Mum passed away only a few years ago.

She too became a weight inside of a grey plastic box, which I buried at that same Memorial Garden.

I wondered how many thousands of grey boxes must have been in the soil around me.

I resolved that I try hard to visit both she and Hamish rather than tooting a car horn as I drove by. I’m not sure I’m any better at my visits than anyone else.

Mum’s inheritance and her experience have actually shaped and allowed for the creation of this business Reterniti. I owe her.

I would have liked Mum to be closer to me instead of that grey box.

But her legacy is much more enduring now.

Reterniti has become a modern way of remembering.

Of keeping them close.

And of delaying for as long as we can, the day of the last utterance of a loved one’s name.

Peter Russell, Reterniti Founder.